© 2023-2025 CHE

Andrey Schetnikov

PRINCIPLES OF CONSTRUCTING GIRIH GEOMETRIC ORNAMENTS

Islamic geometric pattern is an art where beauty, geometry, and intellect come together. Patterns made of stars and interlacing lines decorate mosque mihrabs and minbars, the entrances and iwans of madrasas and caravanserais, as well as palaces and mausoleums. Such ornaments can be found across a wide region — from northern India to Morocco and southern Spain.

This art began in the Samanid state in the 10th century, on the land of today’s Uzbekistan and nearby countries. The patterns we see in Samarkand and Bukhara belong to a later time, the 14th–16th centuries, created under Amir Timur, his grandson Ulugh Beg, and their successors. The ornaments of Khiva, with their complex plant-like designs, were made in the 19th century. We even know the name of one Khiva master — Abdulla, called “the genius.”

This art is not linked to any single ethnicity. The same pattern can appear in Delhi and Herat, Isfahan and Cairo, Aleppo and Granada. Its main rule is symmetry: a fragment repeated again and again through reflections, shifts, and rotations. The makers of these ornaments were educated people — architects and thinkers who studied Euclidean geometry and were inspired by Pythagorean and Platonic ideas. Ornament begins in the world of lines and numbers, and then takes shape in brick, stone, mosaic, or glazed tile. At first, the designs were monochrome, created through relief and shadow. Later, color appeared — azure, aubergine, and finally multicolored decoration. Geometric patterns, called girih in Persian, often became mixed with plant ornament, known as islimi.

Looking at pattern, we feel that strict logic lies behind the beauty. A true master is not one who simply makes a complicated pattern, but one who invents a new rule or principle that gives the design a fresh, unseen face. It is like poetry: limited in form, but able to vary endlessly, like the verses of Eastern ghazals.

Islamic geometric pattern is also a space for intellectual play. Why not just follow the fixed tradition? Why not repeat the things that already exist? Perhaps because the tradition itself encourages invention — the mental work of creating a visual system without words.

These patterns do not hide secret codes or messages. Their meaning lies in the diversity that grows out of unity. They show harmony — the harmony sought by Pythagoras, not as a mystery, but as something alive and reproducible in thought. “Hidden harmony,” said Heraclitus, “is better than the obvious.” When we look closely at an ornament, the question is not “how was it built,” but “how was it invented.”

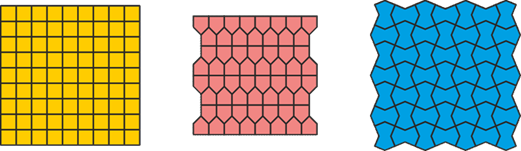

Researchers usually divide girih patterns into three groups by symmetry:

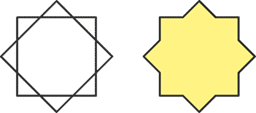

Family No. 1: The Eight-Pointed Star

The basic form is the eight-pointed star, created by overlapping two squares at a 45° angle. This type appears, for example, in the ornaments of the Seljuk Sultanate.

This art began in the Samanid state in the 10th century, on the land of today’s Uzbekistan and nearby countries. The patterns we see in Samarkand and Bukhara belong to a later time, the 14th–16th centuries, created under Amir Timur, his grandson Ulugh Beg, and their successors. The ornaments of Khiva, with their complex plant-like designs, were made in the 19th century. We even know the name of one Khiva master — Abdulla, called “the genius.”

This art is not linked to any single ethnicity. The same pattern can appear in Delhi and Herat, Isfahan and Cairo, Aleppo and Granada. Its main rule is symmetry: a fragment repeated again and again through reflections, shifts, and rotations. The makers of these ornaments were educated people — architects and thinkers who studied Euclidean geometry and were inspired by Pythagorean and Platonic ideas. Ornament begins in the world of lines and numbers, and then takes shape in brick, stone, mosaic, or glazed tile. At first, the designs were monochrome, created through relief and shadow. Later, color appeared — azure, aubergine, and finally multicolored decoration. Geometric patterns, called girih in Persian, often became mixed with plant ornament, known as islimi.

Looking at pattern, we feel that strict logic lies behind the beauty. A true master is not one who simply makes a complicated pattern, but one who invents a new rule or principle that gives the design a fresh, unseen face. It is like poetry: limited in form, but able to vary endlessly, like the verses of Eastern ghazals.

Islamic geometric pattern is also a space for intellectual play. Why not just follow the fixed tradition? Why not repeat the things that already exist? Perhaps because the tradition itself encourages invention — the mental work of creating a visual system without words.

These patterns do not hide secret codes or messages. Their meaning lies in the diversity that grows out of unity. They show harmony — the harmony sought by Pythagoras, not as a mystery, but as something alive and reproducible in thought. “Hidden harmony,” said Heraclitus, “is better than the obvious.” When we look closely at an ornament, the question is not “how was it built,” but “how was it invented.”

Researchers usually divide girih patterns into three groups by symmetry:

- Four-fold (eight-pointed star)

- Five-fold (ten-pointed star)

- Six-fold (twelve-pointed star)

Family No. 1: The Eight-Pointed Star

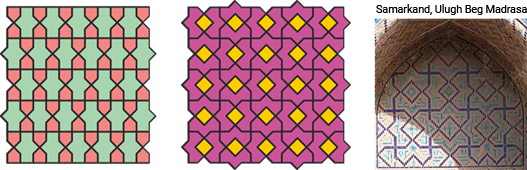

The basic form is the eight-pointed star, created by overlapping two squares at a 45° angle. This type appears, for example, in the ornaments of the Seljuk Sultanate.

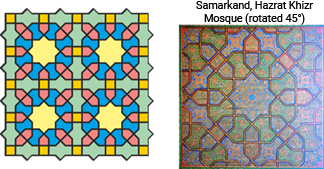

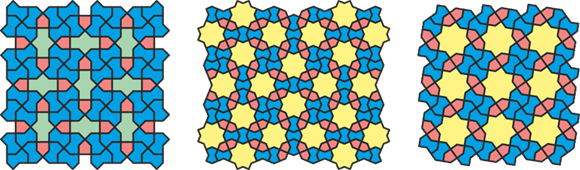

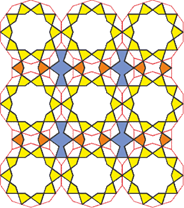

The simplest ornament made from such stars appears when their points are placed next to each other, forming a square grid. In the spaces between the stars, crosses emerge.

Sometimes these crosses are left whole, but more often they are divided into five shapes: four “little houses” and a central square.

Sometimes these crosses are left whole, but more often they are divided into five shapes: four “little houses” and a central square.

If you create a pattern using crosses and squares, another shape appears in the gaps between them — the “pitcher.” Notice that the linework of this ornament is made up of intersecting regular octagons.

Now let’s add a fifth shape to the set of four — the “butterfly.” In this beautiful ornament, known since the 11th century, all five elements of the family are used.

Eight-pointed stars are surrounded by eight “little houses” and eight “butterflies,” forming regular octagons, which in turn are linked together by pairs of elongated octagons.

Eight-pointed stars are surrounded by eight “little houses” and eight “butterflies,” forming regular octagons, which in turn are linked together by pairs of elongated octagons.

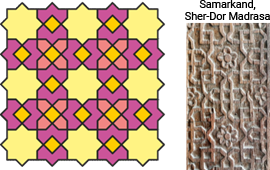

We already have five elements, and in this pattern a sixth appears — a paired set of “paws” that meet across a square. The “paws” can occur in patterns either in such pairs or on their own.

Some elements of this set can form a pattern without the others. Patterns made only of squares or only of “little houses” look rather sparse, whereas a pattern made of “bows” is interesting on its own.

Some patterns are built from a limited number of shapes — for example, only from “bows” or from “paws” combined with squares. Yet even in such cases, visually striking variations are possible. This shows how flexible the system can be, despite its seeming simplicity.

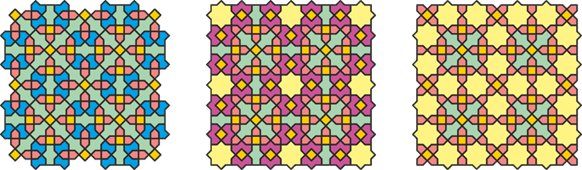

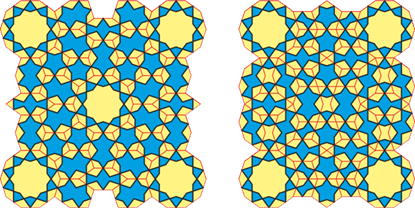

All the patterns in the next illustration are related to one another and are created by substituting some elements for others in various combinations.

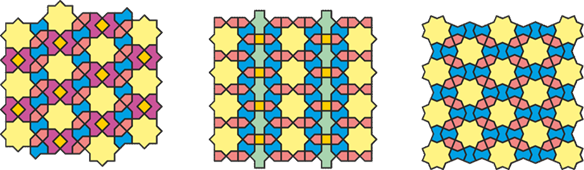

Want to enlarge the size of the cell? No problem — here’s how it can be done:

In the next three patterns, a cluster of four “butterflies” appears, resembling a whirl that can spin either clockwise or counterclockwise. In the first two patterns, the spins alternate in a checkerboard arrangement, while in the third all the whirls are oriented in the same direction.

Combinations of stars, crosses, “little houses,” “butterflies,” “pitchers,” and “paws” create a variety of patterns. These elements form repeating modules that can be arranged in a square grid or in more complex interlocks.

What matters is that all the shapes can be constructed from the same basic fragments, and even a small change in one element produces a new configuration.

What matters is that all the shapes can be constructed from the same basic fragments, and even a small change in one element produces a new configuration.

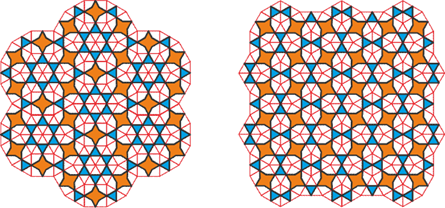

Family No. 2: The Twelve-Pointed Star

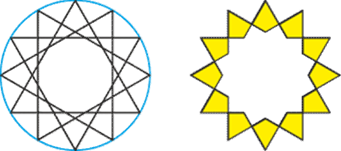

The foundation is a twelve-pointed star inscribed in a regular dodecagon.

To build it, divide a circle into 12 equal parts and connect every third point to the fourth. This creates four equilateral triangles inscribed within the circle.

From each triangle, keep the three quadrilateral “petals” attached to its vertices. Together they form a star with 12 “petals.”

The foundation is a twelve-pointed star inscribed in a regular dodecagon.

To build it, divide a circle into 12 equal parts and connect every third point to the fourth. This creates four equilateral triangles inscribed within the circle.

From each triangle, keep the three quadrilateral “petals” attached to its vertices. Together they form a star with 12 “petals.”

In the first pattern, the stars are grouped in threes, and small equilateral triangles are placed in the gaps between them. Then we add one more step: outline each star with a regular dodecagon. This makes each small equilateral triangle part of a larger equilateral triangle.

In the second pattern, the same stars are grouped in fours. The spaces between them are filled with four equilateral triangles and a four-pointed star framed by a square.

In the second pattern, the same stars are grouped in fours. The spaces between them are filled with four equilateral triangles and a four-pointed star framed by a square.

Now we have three elements: a twelve-pointed star within a dodecagon, a four-pointed star within a square, and an equilateral triangle within a larger triangle.

In fact, we can create patterns without stars — using only triangles or only squares — but such compositions look rather simple. More expressive ornaments emerge when squares and triangles are combined together.

In fact, we can create patterns without stars — using only triangles or only squares — but such compositions look rather simple. More expressive ornaments emerge when squares and triangles are combined together.

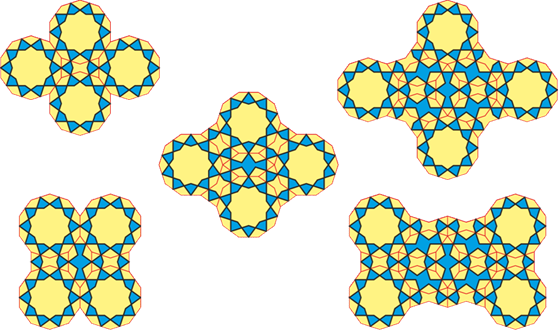

To move forward, let’s make two assemblies: one from three stars and another from four, linking them with a block of four equilateral triangles and a four-pointed star.

Between the three stars, an open space appears, into which a triple “swallowtail” is fitted, framed by an equilateral hexagon with alternating angles of 90° and 150°. In the space between four stars, four of these elements are placed.

Between the three stars, an open space appears, into which a triple “swallowtail” is fitted, framed by an equilateral hexagon with alternating angles of 90° and 150°. In the space between four stars, four of these elements are placed.

From the triangular assemblies, a pattern can be built on a triangular grid, and from the square ones — on a square grid. It is also possible to create patterns that combine both types of assemblies: triangular and square.

There are also patterns that include both triangular and square assemblies, built according to the very same principle that was used earlier with the basic triangular and square cells.

A large “rosette” made from such assemblies looks very elegant, showing the possibilities of a system built from only four elements.

Now let’s surround the star with twelve triangles, place twelve squares between them, and add twelve pairs of triangles on the outside. This creates a large, beautiful rosette. Such rosettes can also be joined together, allowing the pattern to grow further.

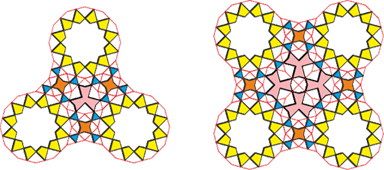

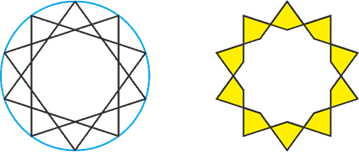

Family No. 3: The Ten-Pointed Star

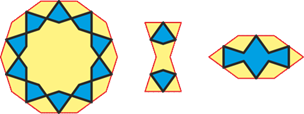

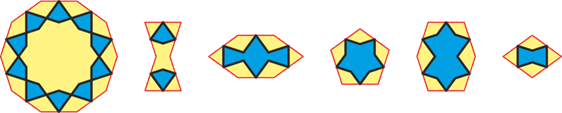

A plane cannot be tiled with regular pentagons or decagons, which makes working with this family especially intriguing. To form a ten-pointed star, connect every third point around a circle. Then transform it into a “necklace” of ten quadrilaterals.

A plane cannot be tiled with regular pentagons or decagons, which makes working with this family especially intriguing. To form a ten-pointed star, connect every third point around a circle. Then transform it into a “necklace” of ten quadrilaterals.

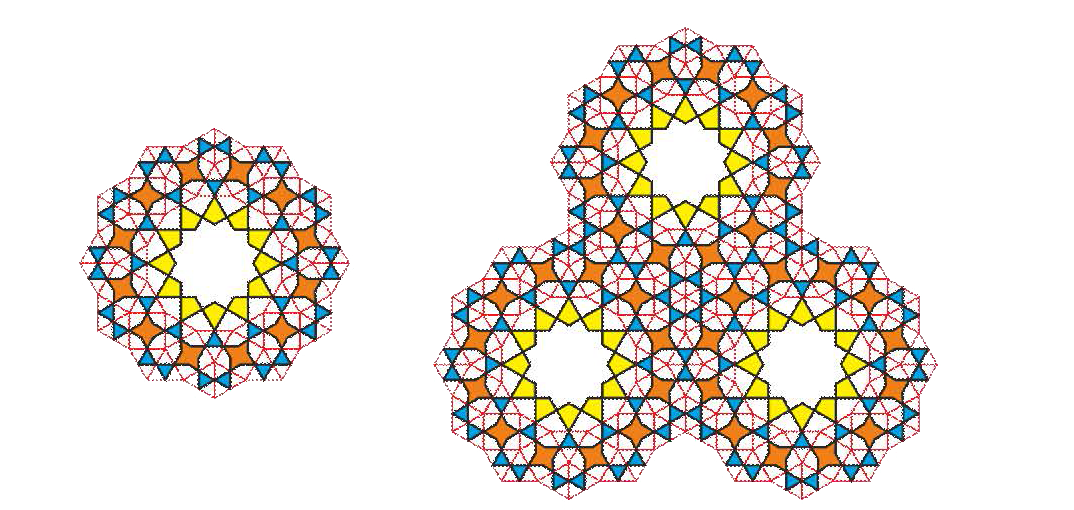

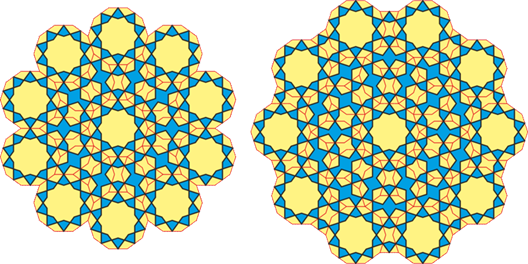

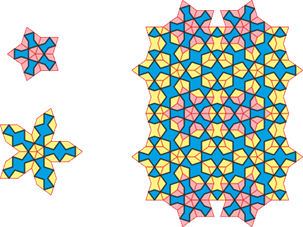

By joining four such stars at the tips of their rays, a “rhombic cell” can be assembled. In the gaps between the stars, two quadrilaterals are inserted — the same type as those within the stars themselves. This gives the design a special refinement. Regular pentagons also appear in the composition, surrounding each star.

Next, enclose the ten-pointed stars within regular decagons. The pairs of quadrilaterals take on casings shaped like “bow ties.”

Next, enclose the ten-pointed stars within regular decagons. The pairs of quadrilaterals take on casings shaped like “bow ties.”

Let’s again take four such stars and arrange them into a “rectangular cell.” In one direction, the stars connect at the tips of their rays; in the other, they are linked through pairs of quadrilaterals. A new figure is placed in the center — the “pitcher,” whose outline resembles a “candy” in a paper wrapper.

The three elements from these two patterns— the ten-pointed star inside a decagon, the pair of “petals” inside a “butterfly,” and the “pitcher” inside the “candy” — together form a system known in Persian as Kond (“blunt”), named after the 108° obtuse angle at the tip of the ten-pointed star in its “necklace” of quadrilaterals. All the contact angles between the inner figure and its frame measure 72°, and the frames themselves are polygons with equal sides and angles that are multiples of 36°.

A great variety of patterns can be created from these elements. Several “rhombic” and “rectangular” cells are shown in the illustration. They connect with one another and fill the plane.

We should also mention ornaments that do without the star and are built from only two elements.

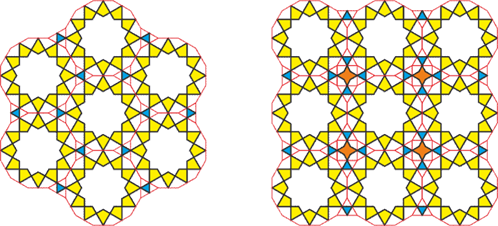

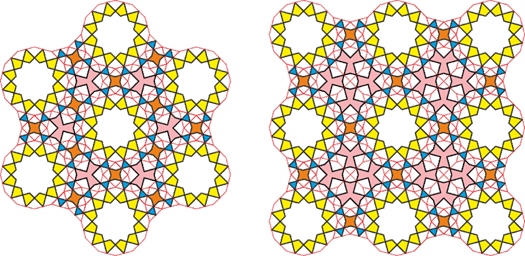

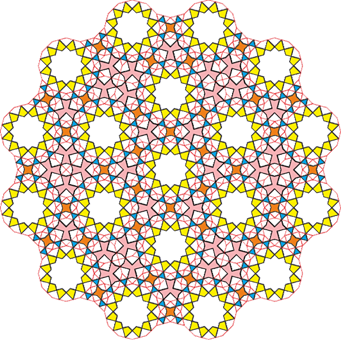

By surrounding the central star with “bows” and “candies,” large rosettes with 10-fold symmetry can be assembled. Patterns with large cells are then created from these rosettes.

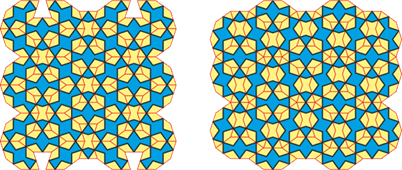

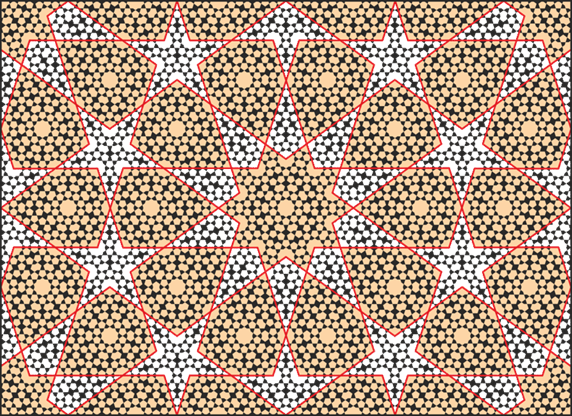

An example of such a pattern is the two-level pattern from Isfahan. On the lower level, it is built from the three elements described above, while on the upper level another system appears — Tond (“sharp”), where the acute angle at the star’s tips measures 36°.

The principle behind this two-level pattern is that at the center of each large element lies the rosette discussed earlier, and at every bend of the pattern’s lines ordinary ten-pointed stars are placed.

The principle behind this two-level pattern is that at the center of each large element lies the rosette discussed earlier, and at every bend of the pattern’s lines ordinary ten-pointed stars are placed.

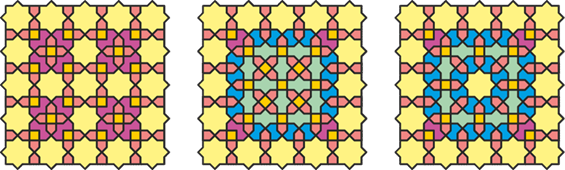

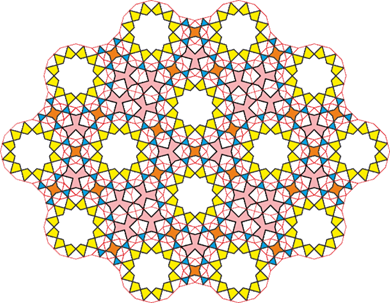

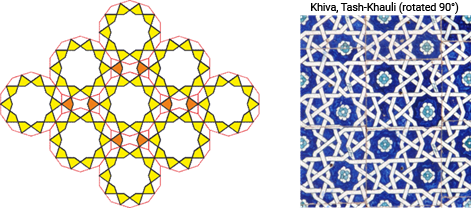

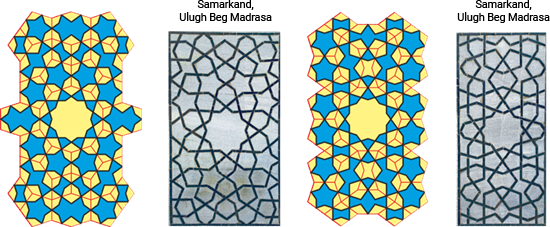

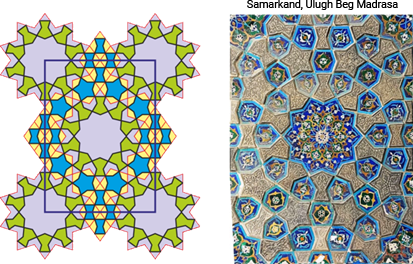

Now let’s add three more elements: a five-pointed star inside a pentagon, a six-pointed figure inside a “barrel,” and a “drum” inside a rhombus. Compositions made from these six elements form a mixed system called Kond & Shol — “blunt and medium,” where the blunt angle measures 108° and the medium one 72°.

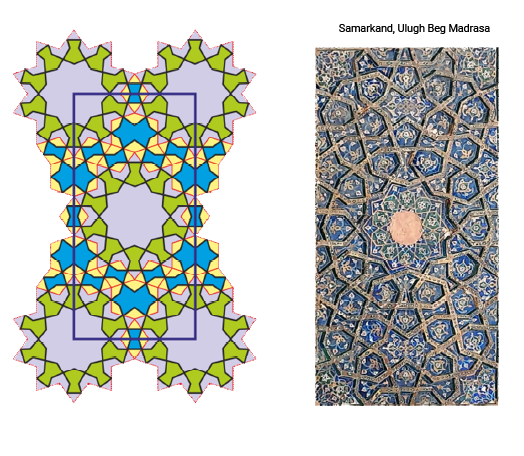

In two patterns from the Ulugh Beg Madrasa in Samarkand, all six elements of the mixed system are present. In the first, the stars are oriented horizontally; in the other, vertically — and this sets the orientation of the entire structure.

Next come the cells of two more patterns in the same style.

In another pattern, two remarkable structures with five-fold symmetry appear: a star made of five “rhombi” or “drums,” and a star made of five “candies” or “pitchers.”

Earlier we mentioned that the constructive set of the Kond & Shol system consists of six elements. But in the Ulugh Beg Madrasa in Samarkand there are two patterns that also include a seventh element — a rosette embedded within a large ten-pointed star. In the first pattern, the tiling is made up of pentagons and quadruple rhombi.

And in the second pattern, the tiling is composed of barrels and rhombi.